A few years ago, a Florida mom, Janine Lutz, told the Marine Corps Times about her son Janos “John” Lutz, who enlisted when he was 19, served on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan, was medically retired in 2011, and died by suicide in 2013 at age 24.

After her son’s death, Lutz established the Cpl. Janos V. Lutz Live to Tell Foundation, which aims to decrease veteran suicide as a result of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – one of the conditions her son was diagnosed with – by raising awareness and providing support for returning veterans. Lutz and others similarly impacted also advocate for more, and better, government-provided suicide prevention resources.

“The United States Marines train our combat veterans for 1 year to become experts in the application of violence but they failed to untrain them so they could reintegrate back into society,” she wrote on her nonprofit organization’s website.

Healing “invisible war wounds”

PTSD, major depression, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and other traumas inflicted by war that aren’t immediately apparent to the eye are often referred to as the “invisible wounds of war.” Unlike physical injuries from combat, they can’t be seen by other service members, family, friends, colleagues, and society in general. Yet they can have a significant impact on the mental health of an active service member or veteran.

While the connection between PTSD and TBI and their impact on suicide ideation and suicide attempt are ongoing topics of research, one study found that veterans with multiple brain injuries are twice as likely to consider suicide compared with those with one or none. Other research that analyzed data from the National Comorbidity Survey showed that PTSD – out of six anxiety diagnoses – was significantly associated with suicidal ideation or suicide attempts.

Suicide rate and US military veterans

The United States Marines train our combat veterans for 1 year to become experts in the application of violence but they failed to untrain them so they could reintegrate back into society”

While the US Department of Defense has been working to better understand and establish resources for active military and veterans at risk for suicide, deaths due to suicide are still a tragic piece of the US military’s story.

In 2023, there were approximately 15.8 million military veterans in the United States — about 6.1% of U.S. adults. Every day, about 18 of those veterans die by suicide, according to the 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, compiled by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

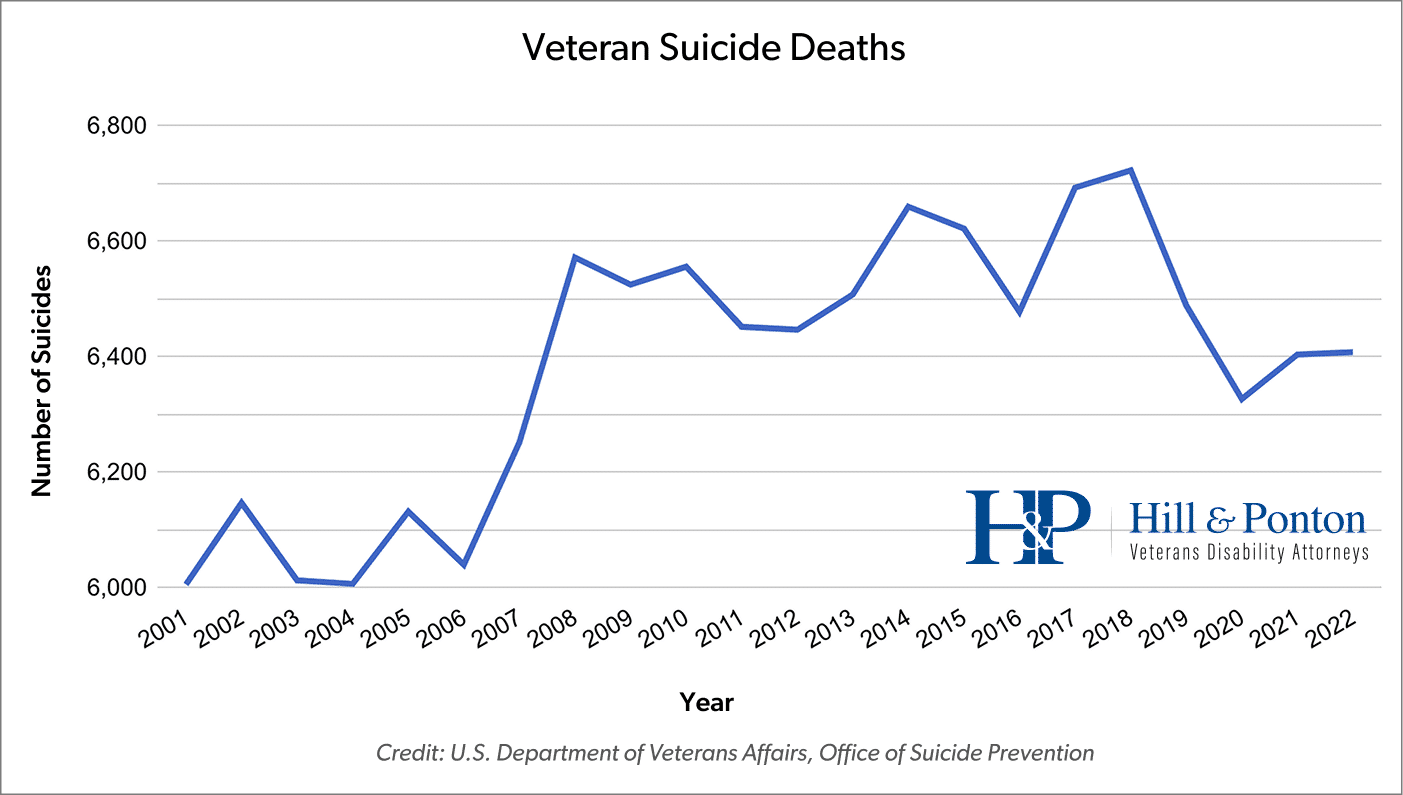

Suicide rates among veterans have climbed since 9/11, the VA reports. In 2001, the suicide rate for veterans was 23.3 per 100,000. By 2022, that figure had increased to 34.7 per 100,000 veterans.

The table below details variation in the number of Veteran suicides, by year from 2001 to 2022

Suicide was the 12th-leading cause of death for Veterans in 2022, and the 2nd-leading cause of death for Veterans under age 45-years-old.

What’s more, veterans die by suicide at a higher rate than the national average, according to the VA. In 2020, the age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate among veterans was 57.3% higher than the age- and sex-adjusted rate among non-veteran U.S. adults.

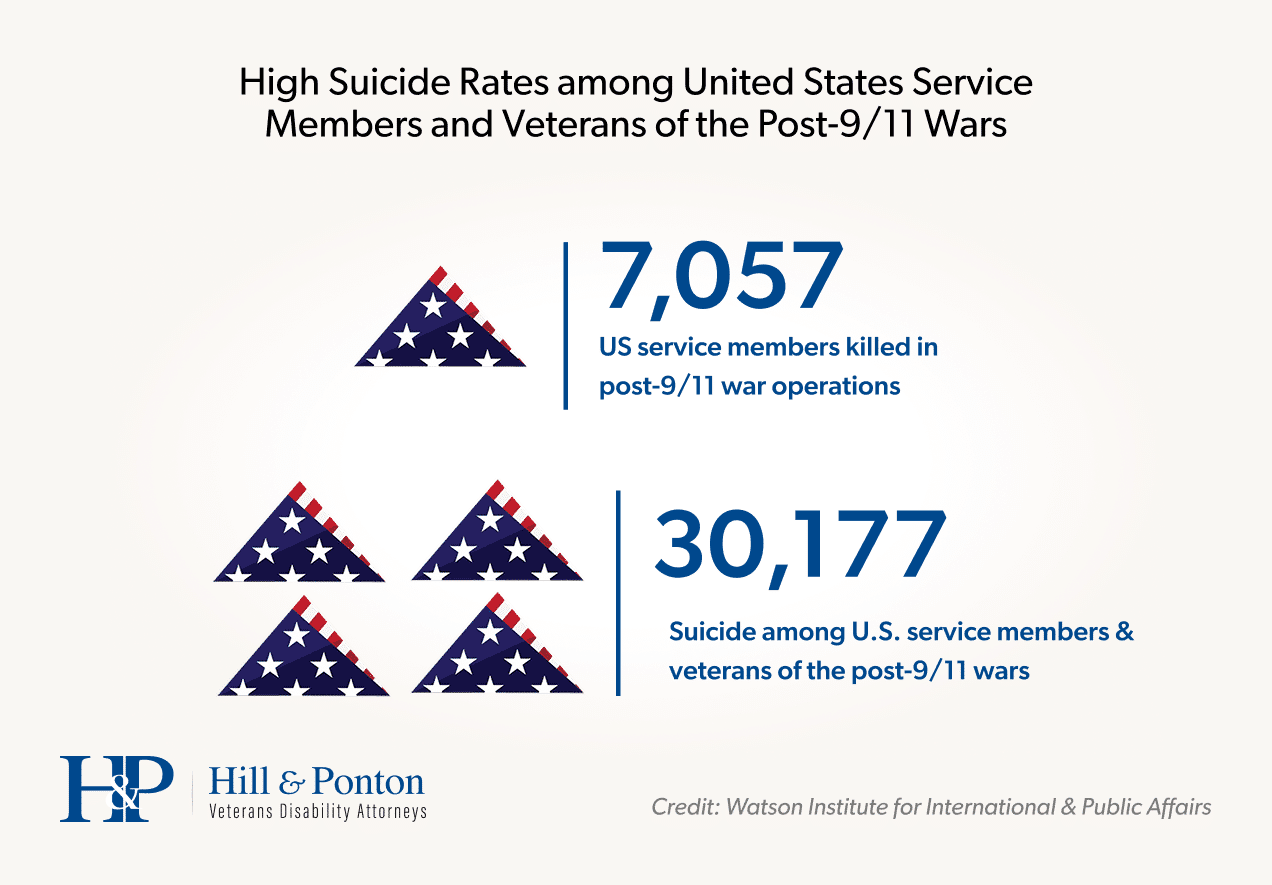

In his 2021 paper for Brown University’s Cost of War Project, Thomas Suitt’s findings indicate that the years after war are more lethal than war itself. Suitt estimated that “30,177 active duty personnel and veterans of the post 9/11 wars have died by suicide, significantly more than the 7,057 service members killed in post-9/11 war operations.”

In an interview with NPR in 2021 when the paper came out, Suitt said, “Even the very conservative estimate that I came up with, it’s horrifying.”

Suicide rates by race and ethnicity

In the VA’s 2022 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, unadjusted Veteran suicide rates were reported by race. The suicide rate was highest among White Veterans at 34.2 per 100,000. The suicide rate was 30.2 per 100,000 among Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander veterans; 29.8 per 100,000 among American Indians or Alaska Native veterans; and 14.2 per 100,000 among Black or African American veterans.

According to an analysis by Military.com, when tallied by percentages, rates of suicide are higher among veterans who are in racial minority groups. A 2024 article on the site stated, “Based on data from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Defense Department, the suicide risk among service members and veterans of Asian American and Pacific Islander descent (AAPI) was 350% higher than the national average, and the per capita rate for Black and Hispanic vets and troops was twice the national average in 2021, the last year for which data was available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, VA and DoD.”

Female veterans and suicide

Suicide deaths among female veterans are different in some ways – including a drop in deaths. According to the 2024 VA report, in 2022, there were 271 suicides among female veterans (80 fewer than in 2021) compared to 6,136 among male veterans (83 more than in 2021). The poisoning suicide mortality rate was higher for female veterans than for male veterans, who were more likely to die by suicide by firearm and suffocation. But the firearm suicide rate among female veterans was 144.4% higher than for female non-veteran adults.

Experiencing sexual trauma while in the military is also associated with suicide. Among female veterans who used VA health services, the suicide rate was 75.0% higher for those who screened positive for military sexual trauma …”

Experiencing sexual trauma while in the military is also associated with suicide. Among female veterans who used VA health services, the suicide rate was 75.0% higher for those who screened positive for military sexual trauma (24.95 per 100,000) than for female veterans with negative screens (14.26 per 100,000).

In her book “Hollow: A Memoir of My Body in the Marines,” Bailey Williams – who was 18 when she joined the Marine Corps, leaving behind a strict Mormon upbringing – talks about the trauma of sexual assault during her time in the Marines. And keeping silent about it. In a 2024 interview on NPR’s “Fresh Air” show, Williams said, “I felt that it would not be taken seriously.” Or if it was taken seriously, she said, “It was going to be my life that got harder and not his.”

Active military and suicide

Veterans aren’t the only ones at risk. In 2023, 523 active service members died by suicide – more than the previous year (493), according to a Department of Defense Annual Report on Suicide in the Military released in November of 2024. Firearms were the primary method of suicide death for service members (65%). The report also noted that suicide rates among active service members have gradually risen since 2011, and that most were young, enlisted men.

Risk factors for suicide

Studies, medical experts, and VA reports have pointed to a broad range of risk factors and issues associated with suicidal thinking (ideation) and suicide among active service members and veterans. They include PTSD, TBI, sexual trauma experienced while serving in the military, multiple deployments, recent transition from military service to civilian life, pain, sleep problems, homelessness, alcohol and substance use, dishonorable discharge, job loss, relationship loss, prescription mismanagement by medical providers, prescription misuse, and lack of a social safety net such as colleagues, family, and friends.

A study in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine found that non-routine service discharge – discharges due to misconduct, personality disorders, and alcohol and substance use disorders – also predict elevated risk for suicidality.

The TBI/PTSD/suicide triad

Of the 5.8 million veterans who served in 2024, about 14 out of every 100 men (14%) and 24 out of every 100 women (24%) were diagnosed with PTSD.

Suitt and other experts have noted that the rise in the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on the battlefield since 9/11 (and compared to mid-20th century and earlier wars) has led to a rise in TBIs, which in turn have been associated with suicide risk.

A 2021 article in NCO Journal, the official publication for non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in the US Army, noted that TBIs are often accompanied by other injuries, both physical and/or mental. This is referred to as polytrauma. According to the article, “Common polytrauma from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars included PTSD and depression along with TBIs. In a recent clinical study of more than 16,000 veterans with deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan, nearly 25% suffered from PTSD, TBI, and chronic pain, more than any other singular condition or combination. This triad of PTSD, TBI, and chronic pain has also been associated with increased suicide rates among veterans.”

Raising awareness, providing support

In The White House’s 2021 Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide strategy, President Joe Biden wrote, “What signs did we miss? What more could we have done?” And the document calls suicide among service members, veterans, and their families a national crisis and complex problem with no single solution.

Some of the efforts the VA, Department of Defense, CDC, the White House, and nonprofit organizations are committed to over the next decade include:

- Foster a supportive environment for active service members

- Improve delivery of mental health care to active service members and veterans

- Address stigma and other barriers to care

- Update suicide prevention training within the DoD

- Promote and ensure firearm safety and storage

- Expand access to suicide hotlines and mental health providers for service members, veterans, and their families

- Ongoing research to better understand suicide risk in the military

- Increase community-based programs, including those that connect veterans

- Improving resources that connect veterans to stable jobs and housing

- No-cost health care for veterans. As of Jan. 17, 2023, veterans in acute suicidal crisis are able to go to any VA or non-VA health care facility for emergency health care at no cost – including inpatient or crisis residential care for up to 30 days and outpatient care for up to 90 days. Veterans do not need to be enrolled in the VA system to use this benefit. https://news.va.gov/press-room/starting-jan-17-veterans-in-suicidal-crisis-can-go-to-any-va-or-non-va-health-care-facility-for-free-emergency-health-care/

Resources for Veterans and Their Families, and Friends

-

Awareness information (for individuals at risk, family, friends, and colleagues) Practice SAVE – Signs, Ask, Validate, Encourage/Expedite

https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov -

Emery Healthcare Veteran’s Program https://www.emoryhealthcare.org/centers-programs/veterans-program

Treats post-9/11 veterans confidentially and at no cost who have conditions including PTSD, TBI, military sexual trauma, anxiety, and depression -

Health Care for Re-entry Veterans (HCRV) program https://www.va.gov/homeless/reentry.asp

HCVR helps to connect justice-involved veterans with VA and community services as they transition from incarceration into the community, facilitating access, to and engagement in, care. A recent analysis found that 56% of veterans seen by the HCRV program engaged with VA health care the following year, and that 93% of those diagnosed with a mental health condition entered treatment for that condition within a year. While this program illustrates the success of current efforts, greater efforts to enhance suicide prevention among this population of veterans remain necessary. - National Call Center for Homeless Veterans https://www.va.gov

- National Center for PTSD https://www.ptsd.va.gov/

- Real Warriors Campaign https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Real-Warriors-Campaign Established in 2009, and expanded in 2023, the Department of Defense’s (DOD) Real Warriors Campaign (RWC) is a public health campaign designed to decrease stigma, increase psychological health literacy, and open doors to access to care by encouraging psychological health help seeking among active duty service members, veterans, and their families.

-

The Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) Hosts Fireside Chats to discuss the role of leaders in preventing sexual assault and harassment.

https://www.dspo.mil/Home/Tools/Fireside-Chats/ - The VA’s National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide provides a roadmap for how the VA is working to change the trajectory of suicide among veterans.

- Stop Soldier Suicide https://stopsoldiersuicide.org/ Their ROGER wellness service provides counseling, crisis intervention, and suicide prevention–100% free for U.S. veterans and service members.

- Veterans Crisis Line Dial 988, then press 1 – https://www.veteranscrisisline.net or Text 838255

-

Veterans Justice Outreach Programs https://www.va.gov/homeless/vjo.asp

To identify justice-involved veterans (incarcerated or recently released) and contact them through outreach to help with access to VA services as early as possible. -

USO Reading Program https://www.uso.org/programs/uso-reading-program

A project to increase social connection and decrease loneliness, it gives service members stationed around the world the opportunity to read and record their child’s favorite bedtime story.