Burn pits were widely used during U.S. military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and surrounding areas to dispose of waste due to a lack of adequate infrastructure. Post-exposure, thousands upon thousands of veterans have reported diseases impacting their lungs and breathing, as well as other ailments, as a result of having been exposed. Thanks to the PACT Act, some of those illnesses are now presumptive, making it easier for veterans to claim VA disability benefits.

The Dangers of Burn Pits

Burn pits were originally a temporary solution in U.S. military base camps to the build-up of refuse and waste until incinerators and other permanent solutions were built. Unlike incinerators used in the U.S., burn pits in military zones lacked restrictions on what could be burned. As a result, toxic materials were routinely incinerated in open-air pits:

- Electronics and batteries (including lithium)

- Rubber and plastics (like Styrofoam)

- Pesticides and paints

- Human and medical waste (including amputated body parts)

- Munitions and fuel derivatives

Such uncontrolled burning led to significant toxic exposures, particularly for veterans who lived or worked in proximity to the burn pits. The byproducts of combustion included known health hazards: particulate matter, heavy metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), dioxins, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Airborne Hazards

Burn pits expose veterans to airborne hazards called “particulates” which are small particles of residue from the debris in the burn pits that are inhaled by those in the area of the smoke plume. These particulates settle in the lungs and can cause a myriad of health problems based on what the particulate is composed of or has transformed into due to incineration. Not only can these particulates cause respiratory and lung issues; but the chemicals they become when they are burned can also cause illnesses within the rest of the body that may not show up for years.

Burn Pit Exposure Symptoms and Related Conditions

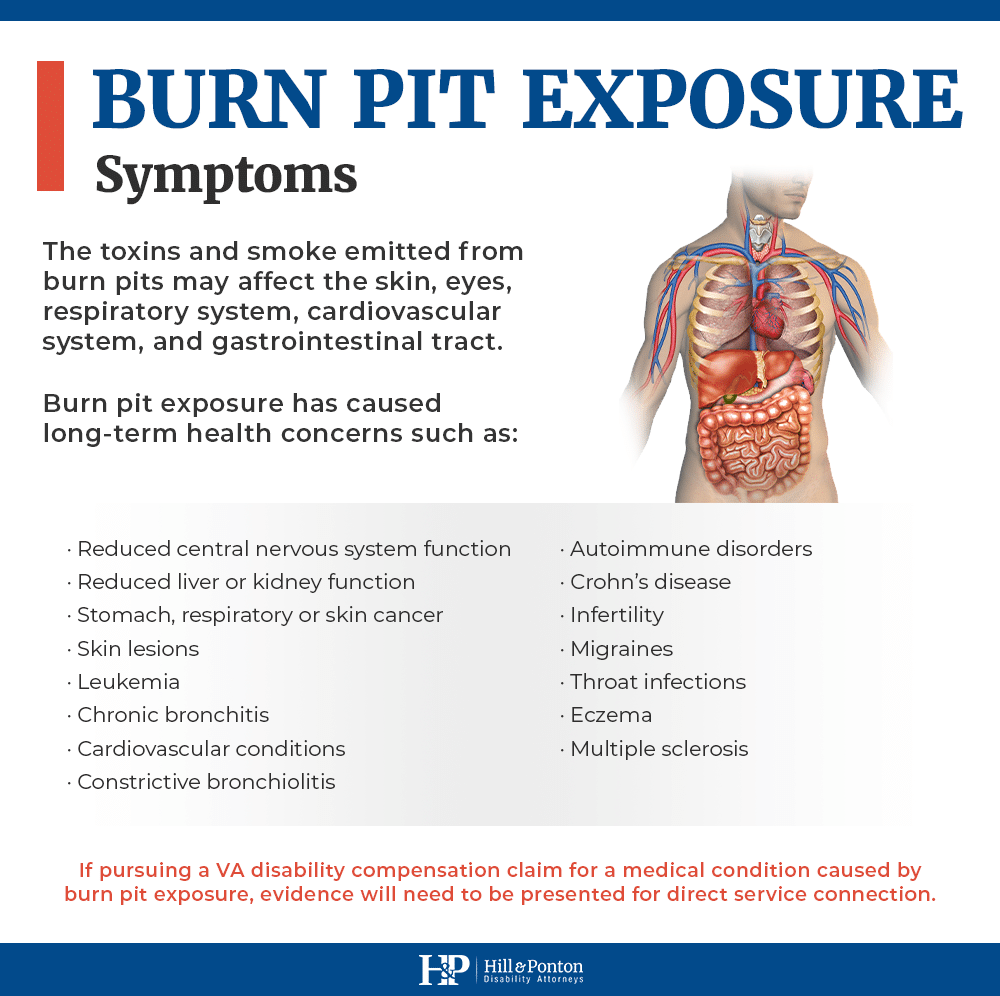

The toxins and smoke emitted from burn pits may affect the skin, eyes, respiratory system, cardiovascular system, and gastrointestinal tract. Initial exposure symptoms often include:

- eye irritation and/or burning

- coughing and throat irritation

- difficulty breathing

- skin itching

- rashes

These exposure symptoms often appear temporary and resolve following initial exposure. However, burn pit exposure has caused long-term health concerns as well, particularly respiratory issues, autoimmune disorders, and cancers. Veterans with pre-existing lung or heart conditions, or who had extended deployments near large burn pits, may face greater risks.

Presumptive Conditions from Burn Pit Exposure

The PACT Act of 2022 significantly expanded the list of presumptive conditions linked to burn pit and airborne toxin exposure for Gulf War and Post-9/11 veterans. Veterans no longer need to prove a specific link between service and illness for these conditions – the VA presumes causation if eligibility requirements are met.

Presumptive Cancers Related to Burn Pits

- Brain cancer

- Gastrointestinal cancer (of any type)

- Glioblastoma

- Head cancer (any type)

- Kidney cancer

- Lymphatic cancer (any type)

- Lymphoma (any type)

- Melanoma

- Neck cancer (any type)

- Pancreatic cancer

- Reproductive cancer (any type)

- Respiratory cancer (any type)

Presumptive Respiratory Conditions

- Asthma (diagnosed after service)

- Chronic bronchitis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Chronic rhinitis

- Chronic sinusitis

- Constrictive or obliterative bronchiolitis

- Emphysema

- Granulomatous disease

- Interstitial lung disease (ILD)

- Pleuritis

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Sarcoidosis

Eligibility for Burn Pit Presumptive Conditions

You can qualify for a presumptive condition if you served in the following locations and time periods:

- Southwest Asia theater of operations (including Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, Egypt) – from August 2, 1990 to August 31, 2021

- Afghanistan, Djibouti, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Uzbekistan, or Yemen – from September 11, 2001 to August 31, 2021

- Somalia – from August 2, 1990 to August 31, 2021

VA’s automatic recognition of burn pit exposure also applies to the associated airspace over any of these countries or waters for the specified time periods.

If you were previously denied benefits for a disability caused by burn pit exposure that is now presumptive, Hill & Ponton may be able to assist you. Get a free evaluation of your case here.

Who Is Eligible for the Burn Pit Registry?

In 2014, the VA has set up the Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry to gather data that will help VA doctors and researchers learn more about how burn pit exposure affects veterans. Registration helps to show patterns of illnesses that spur future research studies for links to exposure and all information is kept in a secure database. The more veterans who register that have similar conditions, the more chances of linking the illness and pursuing presumption for veterans.

If you served in one of the following areas or operations between 1990 and 2021, you may already be in the registry:

- Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan)

- Operation Iraqi Freedom

- Operation New Dawn

- Djibouti (on or after Sept. 11, 2001)

- Southwest Asia theater of operations (on or after August 2, 1990)

The registry will make it easier to study the long-term health effects of those exposed to burn pit particulates as well as other environmental exposures during the Middle Eastern campaigns and within these theaters of operations. If you are not yet included, you can add your name to the registry and create a record of your burn pit exposure, symptoms and medical conditions.

Participation is completely voluntary and doesn’t cost anything. It involves filling out a self-reported questionnaire and potentially a free, in-person VA health exam. Note that the evaluation for the burn pit registry does not replace a C&P exam, and that adding your name to the registry does not initiate a disability claim (see how to make a claim in our free guide).

The registry is simply a way for the VA to track service members who were exposed and contribute to the ongoing research on burn pits and their health risks. However, the questionnaire and the evaluation may be used to support a disability claim.

What To Do If You Were Exposed to Burn Pit Smoke

- Talk to Your Physician: Share your service and exposure history so it becomes part of your medical record. Having evidence of your symptoms and any diagnosed medical conditions may allow you to obtain VA health care and VA benefits. If a veteran has service-related health concerns, they can have an optional medical evaluation done at the VA, but getting an independent medical opinion is vital to proactively identify health concerns and having an expert find scientific links for those conditions to the toxins that the veteran was exposed to.

- Document Your Exposure: Enroll in the Burn Pit Registry to aid scientific study and support your claim history.

- Claim VA Disability: If diagnosed with a presumptive condition related to burn pits, apply for compensation. Find out how to file a VA claim.

- Get Help with Your Claim: If you already filed for VA disability and were denied, you may still qualify under updated presumptive rules – or establish direct service connection. Contact a VA appeal lawyer for a free evaluation of your case.